Entry 8: Sylvia I first read The Savage God, by A. A. Alvarez, in 1974. This book was the first time I had encountered an examination of the subject of suicide which was actually readable and I found myself gripped by the long section on Sylvia Plath, the American poet

who had married Ted Hughes. Now, Hughes I knew, from college lectures, to be a much-admired poet dealing with themes associated with nature and, in particular, the unreflecting savagery of animals- but I knew nothing of his wife’s work.

Seeking out a copy of Ariel, published posthumously in 1965, I started reading, and re-reading, those dark and brilliant poems. I also sought out other poems and works by her, including The Bell Jar, a novel which details the female protagonist’s inexorable mental decline, several suicide attempts, institutionalisation and Electro-Convulsive Therapy. The novel is, obviously, semi-autobiographical and after a year or so I felt impelled to write a song about her, using images from her poems to help construct the lyric.

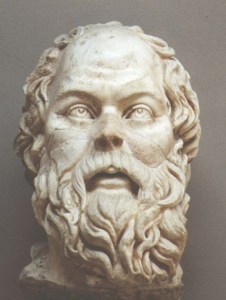

The Greek philosopher, Socrates, argued against suicide, for most part, but ended his life by drinking a hemlock-infused potion: a penalty for having been found guilty of corrupting the youth of Athens and impiety. He saw himself as a gadfly, someone who would sting the state into righteous action. Well, the state reacted as we all do when a stinging insect attacks. Kill it or shoo it away!

The Athenian jurors who voted for the death penalty probably thought that Socrates would take the opportunity to flee before the sentence was to be promulgated. Socrates, however, deeming himself to be a true citizen with a horror of life outside the city-state and obedient to the rule of law, drank the hemlock, turned to his friend, Crito, and said I owe a cock to Asclepius, see that the debt is paid.

He remains the true ideal of an Athenian citizen, reverencing the gods and punctilious about paying debts. Asclepius, is the god of healing and perhaps Socrates is intimating that death releases the soul from the body and its attendant ills, particularly as one ages. Four centuries later in Palestine, Judas flings the blood-money he has accepted for his betrayal of Jesus back at the temple priests and hangs himself in despair. They use the tainted money to buy a potter’s field and bury him there.

betrayal of Jesus back at the temple priests and hangs himself in despair. They use the tainted money to buy a potter’s field and bury him there.

Dante, in The Inferno, places Judas in the deepest circle of hell where Satan chews on his

head eternally. The Gnostics, on the other hand, reasoning that he set in train the salvation of the world, view him as the greatest of all the Apostles. Is there any surprise that one of the most compelling and enduring contemplations of suicide was written 400 years ago by William Shakespeare? You can count in the hundreds of millions the number of people who can complete the line: To be or not to be.

The absence of illness or adversity may not be sufficient to answer the question posed by Hamlet in the affirmative, but clearly if one is suffering the slings and arrows of outrageous Fortune one might choose to end the heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks that Flesh is heir to by taking arms against a sea of troubles, and by opposing, end them. But is it the end? For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come, when we have shuffled off this mortal coil, must give us pause. Indeed, and in that pause do most of us not acquiesce and resign ourselves to grunt and sweat under a weary life because of the dread of something after death, the undiscovered country, from whose bourn no traveller returns, puzzles the will, and makes us rather bear those ills we have, than fly to others that we know not of.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus says: Greater love hath no man than this; that a man lay down his life for his friends. Is this an invitation to martyrdom? A vindication of altruistic suicide? It is certainly a high bar, and one that many have cleared. The stories of soldiers throwing themselves on a grenade to save their comrades and similar tales of heroic self – sacrifice are seen as justifications for self-slaughter by most people. An example of this is

is certainly a high bar, and one that many have cleared. The stories of soldiers throwing themselves on a grenade to save their comrades and similar tales of heroic self – sacrifice are seen as justifications for self-slaughter by most people. An example of this is

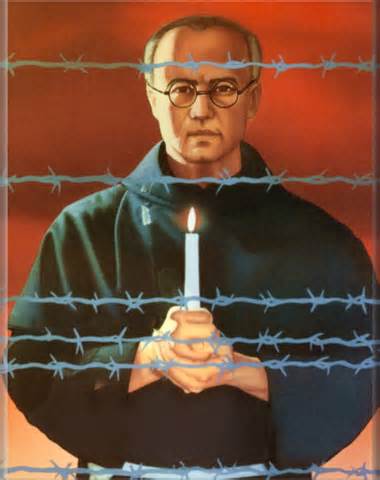

Maximilian Kolbe, a Franciscan priest, who volunteered to take the place of a prisoner who was selected to die of starvation in an underground bunker with nine others as a reprisal for an escape from Auschwitz.

The swap was agreed and Francisek Gajowniczek, who had cried out in anguish for his wife and family, lived for a further 53 years, attending the beatification and later canonisation of Kolbe where the pope at the time, John Paul II, declared him to be a Christian martyr. In 2011, Jessica Council, a 30-year-old pregnant mother, refused cancer treatment in order to give her unborn child the best chance for survival; she died, leaving behind a husband, son and a newborn child who is alive today because of her sacrifice.